Inherited Heavy: Reframing Metal as a Continuum of American Musical Weight (1890–1930)

Abstract

Inherited Heavy examines the historical continuity between early American blues, jazz, and popular song traditions (circa 1890–1930) and modern heavy music. Rather than framing metal as a late-20th-century rupture driven primarily by technology, this project argues that “heaviness” existed long before amplification, distortion, or electric instrumentation. Through metal reinterpretations of early twentieth-century compositions and thematically aligned original works, Inherited Heavy positions heavy music as an inherited cultural expression—rooted in social strain, economic precarity, violence, humor, and survival.

Rethinking “Heavy Music” Before Amplification

Popular histories of heavy music often emphasize technological milestones: electric guitars, distortion, amplification, and postwar studio experimentation. While these developments undeniably shaped modern metal, they did not originate musical heaviness. Instead, they amplified a weight that already existed in American music decades earlier.

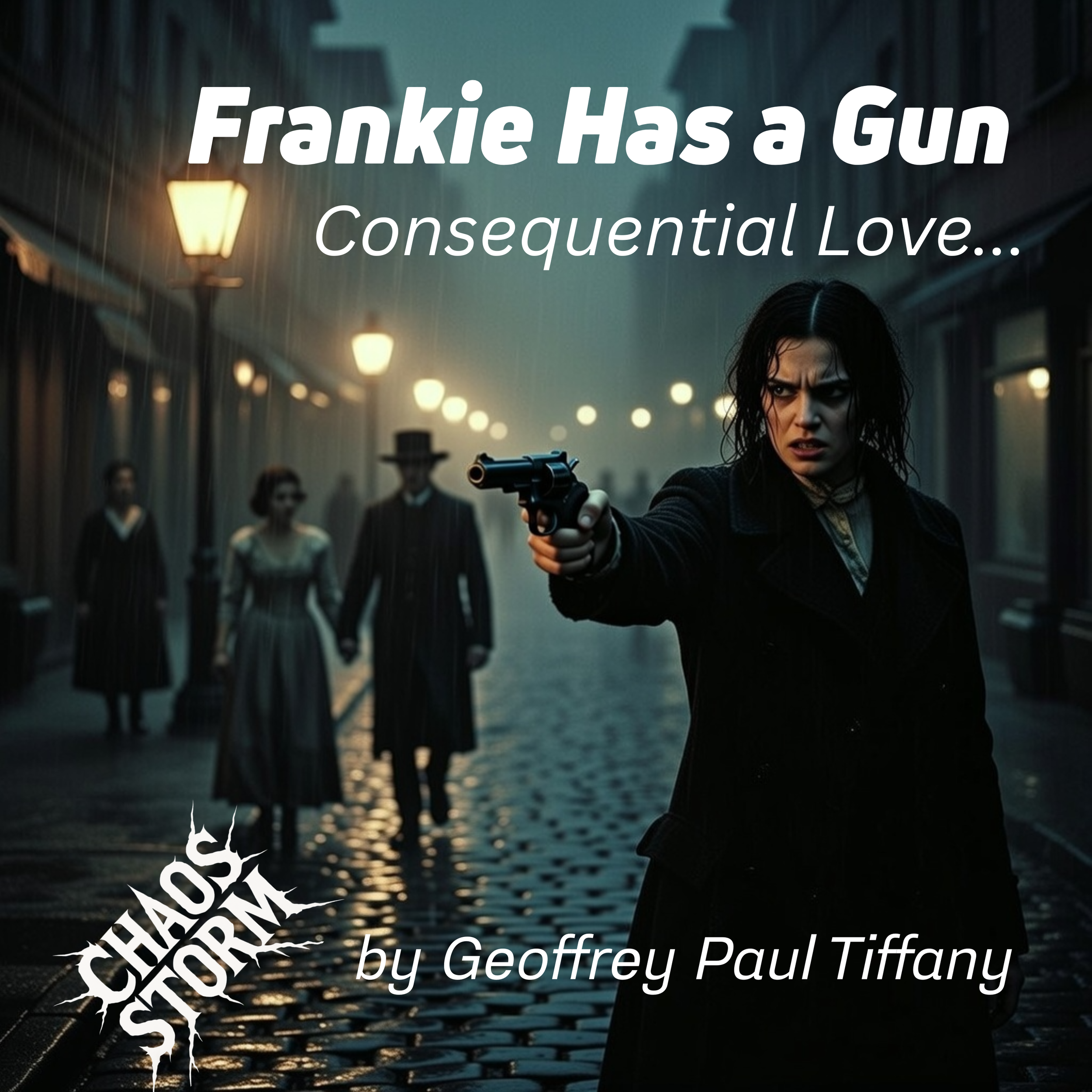

At the turn of the twentieth century, blues, jazz, vaudeville, and popular song frequently addressed themes of betrayal, addiction, incarceration, poverty, racial violence, war trauma, and moral ambiguity. Songs such as “Frankie and Johnny,” “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out,” and “After You’ve Gone” functioned as narrative vessels for lived consequence. Their intensity did not rely on volume, but on inevitability—stories where actions carried irreversible outcomes.

In this sense, heaviness is not a function of sound pressure, but of emotional density and narrative gravity.

Social Conditions and Musical Function (1890–1930)

Between the late nineteenth century and the interwar period, American society underwent rapid and destabilizing change. Industrialization reshaped labor, urbanization intensified social inequality, racial terror remained widespread, and World War I introduced mass trauma on an unprecedented scale. Prohibition further pushed social life underground, intertwining music with criminal economies and informal survival networks.

Music during this period was not merely entertainment. It served social and psychological functions: documenting injustice, processing loss, reinforcing communal identity, and, at times, disguising despair with humor or bravado. Importantly, many songs blended levity and menace simultaneously—a tonal duality that strongly parallels modern heavy and groove-based music.

Narrative Weight as the Precursor to Sonic Weight

Modern definitions of “heavy music” tend to prioritize sonic characteristics: distortion, down-tuned guitars, aggressive percussion, and physical loudness. Inherited Heavy proposes an earlier framework: narrative weight precedes sonic weight.

Under this framework:

A murder ballad is heavy because consequence is unavoidable.

A blues lament is heavy because survival is uncertain.

A comedic jazz standard is heavy because humor masks precarity.

Metal does not introduce these conditions—it translates them using modern tools. Amplification does not create heaviness; it externalizes what was already present.

Metal as Translation, Not Appropriation

The metal adaptations within Inherited Heavy are intentionally conservative in their treatment of lyrical structure and thematic content, while being aggressive in rhythm, texture, and delivery. This mirrors historical patterns of musical transmission: melodies evolve, tempos shift, instrumentation changes, but narrative cores persist.

Original compositions such as “Back From the Fire,” which addresses World War I veterans returning to civilian life, and “Silk Suits & Switchblades,” which explores Prohibition-era criminal mythology, function as connective tissue. They do not modernize history; they continue it, expressing period-accurate themes through contemporary musical language.

Challenging the Myth of Musical Invention

A recurring assumption in popular music discourse is generational exceptionalism—the belief that each era invents its defining artistic forms. Historical analysis suggests otherwise. Musical traditions accumulate; they do not reset. Each generation inherits emotional frameworks shaped by those before it and re-articulates them using available tools.

In this context, metal is not an origin point but a stage in a longer lineage of American musical confrontation with hardship. As articulated in the project’s central thesis:

We didn’t invent it. We inherited it.

This statement is not rhetorical. It reflects a historiographical position that situates heavy music within a continuum of working-class expression rather than isolating it as a technological anomaly.

Conclusion: Heaviness as Cultural Inheritance

Inherited Heavy reframes metal not as a genre defined solely by sound, but as part of a broader American tradition of musical response to pressure, injustice, and survival. When examined historically, early twentieth-century blues and jazz are not precursors to metal in a linear sense—they are early manifestations of the same impulse, constrained only by the technologies of their time.

Metal did not create heaviness.

It learned how to carry it louder.

#MusicHistory #AmericanMusic #CulturalHistory #HeavyMusic #MetalStudies #BluesHistory #JazzHistory #PopularMusicStudies #SoundStudies #CulturalContinuity #MusicAndSociety #WorkingClassCulture #ProhibitionEra #WorldWarIHistory #NarrativeMusic #Ethnomusicology #MusicTheory #ModernMetal #HistoricalAnalysis #BBN31